Bridging the gap: Integrating behavioral science in primary care

- Most primary care visits are reported to be associated with one or the other behavioral issues and have huge influence on morbidity and mortality.1

- Use of behavioral science theories can help understand patient behavior and integrating behavioral health in routine clinical practice can improve patient outcomes.1,2

- Behavioral health can be integrated in routine care using the Collaborative Care Model (CoCM) and Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model, which embed behavioral health professionals in the core care teams.3

Do you know that behavioral issues like tobacco use, poor diet, inactivity, alcohol use, substance abuse, and risky sexual behavior are the leading causes of death, disease, and preventable injuries worldwide?1,4 Almost 75% of primary care visits are reported to be associated with one or more behavioral health-related components.1 Similarly, most chronic diseases are known to be associated with behavioral components.5 Therefore, understanding and addressing behavioral health (BH) issues in routine clinical practice care is pivotal and is referred to as the gold standard of care.1

Why is involving behavior science in clinical practice important?

Health interventions are most effective when they are rooted in behavior change theories.4 Consider a scenario that most of you would have come across in your clinic. A female patient, aged >55 years, is visiting for acute lower back pain. She reports high work-related stress, is hypertensive, overweight, and a smoker. In regular practice, you would prescribe evidence-based medicine for her back pain, encourage her to lose weight, and advise her on healthy lifestyle changes, such as eating a healthy diet, exercising, maintaining good sleep hygiene, and informing her about her risk of cardiovascular disease.6

Will these recommendations be effective?

Will she follow your advice?

Simply prescribing medication and advising lifestyle changes is insufficient. Health behaviors result from individual, interpersonal, societal, and cultural factors. Effective health behavior change requires integrative models that consider all these factors. Behavioral theory organizes knowledge, explains why people adopt or abandon healthy lifestyles, and helps predict and prevent disease and injury, making health programs more effective.2

To learn more about these health behavioral theories, please read our article Methods of behavior change in medication non-adherence. To understand behavioral theories impacting treatment outcomes through non-adherence to medication, listen to our masterclass on Behavioral frameworks for understanding patient adherence and A:Care Congress 2024 session on “Don’t remind me to take my medication”: Exploring behaviors behind medication non-adherence

What is behavioral health integration (BHI)?

Access to high-quality behavioral care is a major challenge in primary healthcare. About 70% of serious behavioral health conditions in primary care usually go undiagnosed and untreated. While some primary care providers (PCPs) are effective at delivering BH care, many lack the training, time, or interest. The traditional model of behavioral healthcare relies on referring patients to external specialists. However, this often fails due to limited access, complex referral processes, and stigma. Furthermore, communication between PCPs and mental health providers is hindered by confidentiality issues, time constraints, and logistical barriers. As a result, 50–90% of referrals never lead to an appointment, and most patients who do schedule care never begin treatment.5

Behavioral Health Integration (BHI) in primary care addresses this health gap. It is widely recognized as a collaborative approach in which primary care providers, psychiatric physicians, and other mental health professionals work closely with patients, families, and caregivers to deliver patient- and family-centered care. BHI has been shown to be particularly effective for patients with mild-to-moderate depression, anxiety, and those undergoing treatment for substance use disorders (SUD).3

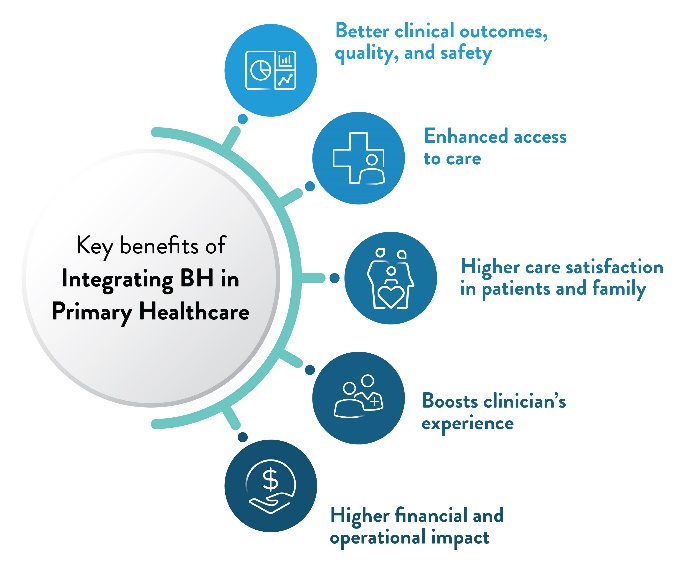

The key benefits of BHI in primary care are:3,7

Better clinical outcomes: Integrating BH enhances whole-person care by addressing both mental and physical health. It supports early identification of common mental and behavioral health issues and improves their management. Additionally, it promotes timely care that can help prevent long-term complications such as self-harm and suicide risk.

Enhanced access to care: BHI reduces barriers to mental health services by bringing care directly into primary care settings. This improves access for underserved populations, reduces stigma, and helps close the treatment gap caused by clinician shortages and systemic challenges like cost, transportation, and cultural barriers.

Higher care satisfaction among patients: Integrated care improves trust and satisfaction by delivering comprehensive services in a single setting. It also strengthens continuity of care, improves health outcomes, and encourages patient loyalty to their healthcare practice.

Boosts clinicians’ experience: With a team-based approach and access to BH resources, clinicians feel more confident and competent in managing mental health concerns. It improves their work satisfaction and reduces burnout, helping to provide care more efficiently and effectively.

Higher financial and operational impact: BHI helps optimize primary healthcare systems by reducing emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit stays. Early identification and treatment of BH issues make it a cost-effective strategy in the long term.

Figure 1: Key benefits of BHI in primary care practice.3

(The image is only for illustration purposes and the content is from

Behavioral Health Integration Compendium by AMA.3)

From theory to practice: Integrating BH in primary healthcare

At one end of the BHI spectrum is coordinated care, where clinicians in different healthcare settings share information about mutual patients, with communication being the key component. At the opposite end is integrated care, where PCPs, psychiatric physicians, and other clinicians collaborate as a unified team, using a systematic and seamless approach to deliver patient-centered care to a defined population.3

The two most widely used models for integrating behavioral science in primary care settings are:

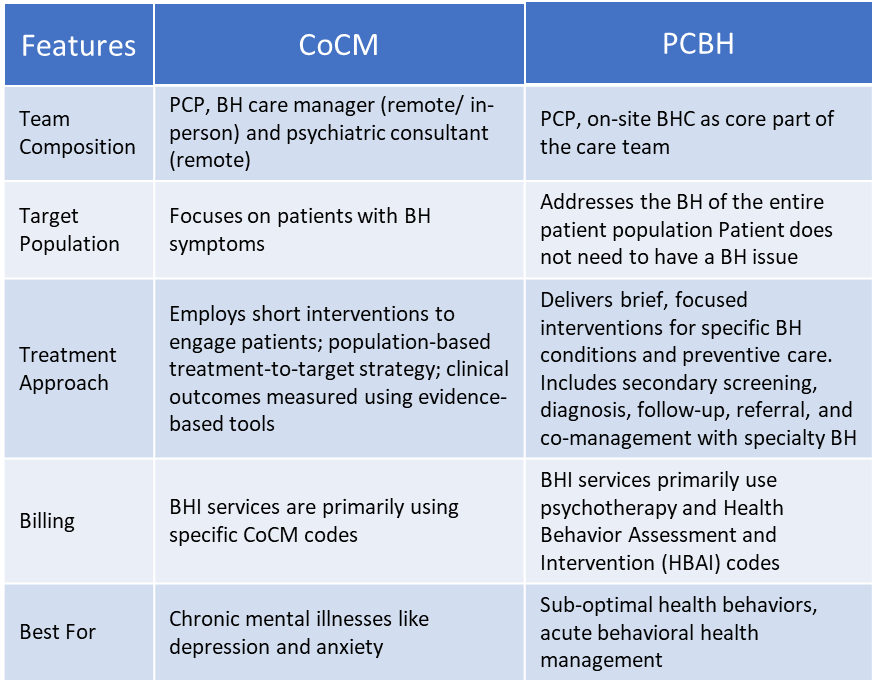

The Collaborative Care Model (CoCM): It is one of the most widely used, evidence-based, and cost-effective approaches for managing BH in primary care. It consists of a central care team, including a BH care manager and PCP working closely together. The BH care manager is typically a master’s-level professional, e.g., a medical social worker (MSW) or licensed clinical social worker (LCSW), or someone with specialized BH training. He coordinates patient care and may consult with a psychiatric specialist (located off-site) as needed. The psychiatric consultant provides weekly reviews of patient panels, focusing on the complicated cases, and makes treatment recommendations through discussions with the care manager. Treatment may involve focused behavioral therapy as well as medications prescribed by the PCP under psychiatric consultation. Patient progress is systematically tracked using screening tools and a practice registry.3,7

Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model: Also known as the Behavioral Health Consultant Model, it is a population-based model. In this model, a BH clinician—such as a PsyD, PhD, MSW, or LCSW—is a core member of the primary care team and plays a key role in implementing practice-wide strategies for prevention, early identification, and intervention. The BHC collaborates with providers during routine visits, offering brief, short-term therapy. They provide targeted treatment for behavioral health conditions, health-risk behaviors that worsen physical health, and chronic medical conditions across all age groups, including pediatric, adult, and geriatric populations. As an integral member of the primary care team, the behavioral health professional shares both the responsibility and accountability for patient care. They manage scheduled appointments with individual patients while keeping their schedule flexible to accommodate same-day “warm handoffs” or other referrals from primary care providers and team members.3,7

Table 1: Comparing CoCM and PCBH models of integrating BH in primary care3,7

BH, Behavioral health, BHC, Behavioral health consultant, CoCM, Collaborative Care Model, PCBH, Primary Care Behavioral Health model, PCP, Primary care physician

Tips for implementing behavioral health in clinical practice

The Behavioral Health Integration Compendium by the American Medical Association (AMA) describes eight elements that are pivotal to integrating behavioral health into routine clinical practice. These building blocks can be used across the integration spectrum:3

- Identify the need and access to BH: All patients should be offered routine, age-appropriate BH screening, and assessment should follow set processes for BH management. There should be provision of same-day access to BH services and patient-centric scheduling.

- Establish a unified care team: For a positive impact on engagement and effectiveness of BH services, it is important to establish a culture of teamwork with clearly defined roles and regular communication within the team.

- Share patient information: It is crucial to share information within the care team, with specialty services, and patient for proper coordination of care. Sharing information with patients helps build trust and encourages their engagement with treatment.

- Use specialist consultants and referral processes: For effective healthcare utilization and to reduce unnecessary specialty referrals, a clear referral process to specialty care should be established. Build protocols for physicians’ easy access to psychiatric consultation services.

- Design population-based care: Identify and define the specific population to be supported with the BH program. Implement a system of routine primary screening to identify those at risk. Adjust treatment plans during follow-up assessment if improvement is not as expected.

- Provide evidence-based treatment: Use evidence-based BH screening tools, interventions, and quantifiable assessment scales while adapting them as per the needs of the specific patient population. Establish a system for regular follow-up visits to gather functional data, set goals of treatment, and encourage self-management strategies.

- Involve family and social support: Engage family and social support for a positive influence on outcomes. Address patient-identified psychological, cultural, social, and physical barriers to care. Implement a patient-centric treatment approach with shared decision-making between patient, family, and caregiver.

- Assess program and establish sustainable model: Systematically track patient feedback and engagement with BH services. Establish a quality improvement structure to achieve set goals and outcomes.

A successful example of BHI: CoCM for pediatric behavioral health

A successful example of implementing CoCM is the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program (MCPAP), which addresses the growing behavioral health needs of children and adolescents.3 With the shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists, the burden of early identification and intervention often falls on PCPs, many of whom feel unprepared to manage complex pediatric mental health concerns.3 Recognizing this gap, MCPAP was launched in 2004 to support PCPs through an innovative, regionally organized CoCM framework. Under MCPAP, child and adolescent psychiatrists partner with primary care pediatricians by providing:8

- Real-time consultation and guidance on diagnosis, psychopharmacology, and treatment planning

- Education and mentorship to enhance the behavioral health competence of PCPs

- Referral support for high-risk or complex cases that require specialty care

This model ensures that behavioral health care is integrated into pediatric primary care and offsets the demand for specialty care. This collaborative approach resulted in mental health screenings for 80% of health supervision visits, and 95% of children in Massachusetts had access to integrated mental health services in their primary care practices.3 The program demonstrates how leveraging psychiatric expertise within a team-based, consultative CoCM structure can expand access, improve early identification, and increase provider confidence in managing pediatric behavioral health without overburdening the limited specialist workforce.

Integrating BH in primary care: A pathway for optimized healthcare delivery

Primary health practitioners should not perceive BHI as an added workload in their already busy schedules; rather, it is an opportunity to optimize primary care efficiency. When implemented effectively, BHI provides timely and appropriate behavioral health resources, enabling clinicians to comprehensively support their patients’ overall well-being. Addressing behavioral issues in primary care through this collaborative approach not only reduces overreliance on primary care providers but also enhances satisfaction for both patients and clinicians by ensuring that care is better aligned with patients’ full spectrum of needs.3

Finally, implementation of BHI in primary care settings is essential to enhance disease outcomes, improve patients’ and providers’ experience, and help reduce overall cost by delivering whole-person care.3,7

BHI embeds behavioral health services directly into primary care, allowing real-time collaboration between PCPs and behavioral health providers. Unlike traditional referrals, BHI promotes shared care plans, timely access, and team-based support within the same system.3

Health conditions like mild-to-moderate depression, anxiety, insomnia, adjustment disorders, substance abuse, and behavioral concerns in children can be effectively managed with BHI support. However, severe or complex cases of mental health and behavioral issues should be referred to specialty care.3

BHI improves workflow by reducing repeated patient visits, allowing behavioral health providers to address patients’ behavioral concerns and freeing up PCP time, thereby improving care coordination.3

BHI services under the CoCM model can be billed using CoCM-specific codes. While BHI services under the PCBH model can be billed using psychotherapy and Health Behavior Assessment and Intervention (HBAI) codes.3

Both models have their value, and the choice depends on the needs of a particular practice. The CoCM is ideal for managing depression, anxiety, and other common conditions with a structured, psychiatric consultant-supported approach. On the other hand, the PCBH model focuses on brief, functional interventions for the whole patient population, often for a broader range of issues. It’s more flexible and workflow-compatible. Many practices combine both approaches and use a hybrid model to maximize impact.7