From aging to action: Behavioral and integrated intervention to improve adherence

- As the 21st century becomes the era of aging, medication nonadherence in the elderly poses a major challenge contributing to economic wastage, lack of disease management, increased hospital admissions, and elevated mortality rates1,2,3

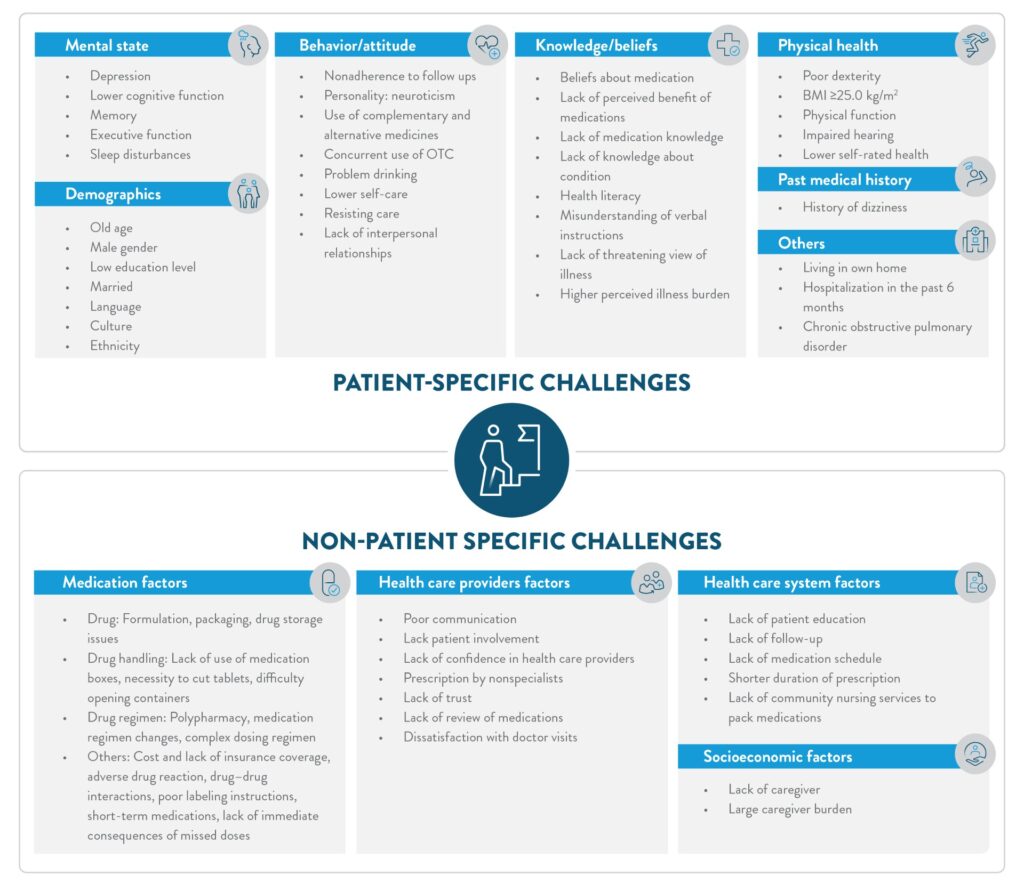

- Medication adherence in the elderly is hindered by two main challenges: patient-specific challenges and non-patient-specific challenges3

- Improving medication adherence in the elderly requires a personalized, multifaceted approach that addresses age-specific barriers, simplifies regimens, and engages both patients and caregivers4

The rising tide of aging and chronic disease in elderly patients

Cindy McDonald aptly stated, “Aging is not an option; it is how gracefully we handle the process and how fortunate we are as the process handle us”1

One of humanity’s most remarkable accomplishments in the last century was the rise in average life expectancy, driven by progress in public health, technology, and medical science. While the 20th century was defined by rapid population growth, the 21st century is poised to be remembered as the era of aging.2 The demographics of the global human population has undergone drastic shifts compared to a century ago.5 Globally, there were 703 million individuals aged 65 years and above in 2019 and this number is projected to double to 1.5 billion by 2050, equivalent to one in six people in the world.6

Elders are increasingly affected by complex health conditions, commonly known as geriatric syndromes, which result from the interplay of multiple underlying factors. Common chronic conditions in this population include hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, osteoarthritis, bronchial asthma, dyslipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy etc. In addition to chronic illnesses, aging individuals frequently experience issues such as cognitive decline, falls and fractures, incontinence, dizziness, and impaired hearing and vision.1,2

Given the complexity of managing multiple chronic conditions, high prevalence of comorbidity and functional impairment, polypharmacy, increased vulnerability to drug-related problems, promoting medication adherence and healthy behaviors in the elderly is critical, as adherence often requires patient education, effective communication, and meaningful belief shifts to initiate and sustain daily regimens successfully.4,7 Poor adherence can lead to suboptimal medical outcomes, such as lower quality of life, more readmissions and poorer clinical outcomes for the elderly.8

Multifactorial challenges of poor medication adherence in the elderly patients

Elder patients often face a unique set of challenges that make consistent medication use more difficult. There are many inter-related challenges for medication non-adherence, and they fall into two main categories:9

- Patient-specific challenges: These are related to the individual’s physical, psychological, and behavioral condition

- Non-patient specific challenges: These are systemic or medication- related factors not directly caused by patients—medication factor, health care providers factors, health care system factors and socioeconomic factors

Figure 1: Challenges of poor medication adherence in the elderly patients (The figure is for illustration purposes only. Adapted from Harris D et. al [2025]3 and Yap AF et. al [2016]9)

To delve deeper into the complexity of adherence behavior, it is helpful to apply the COM-B (Capability-Opportunity-Motivation Behavior) model which helps to understand human behavior by hypothesizing the existence of an interplay between capability, opportunity, and motivation produce a certain behavior. For example, a qualitative study in elderly patients with coronary heart disease applied the COM-B model to identify key adherence barriers: forgetfulness, distractions and fear of side effects (psychological capability), inaccessible medication and difficulty renewing prescriptions (physical opportunity), concerns about burdening family (reflective motivation), and medication fatigue, health decline (automatic motivation). The study also found that digital tools like text messaging and mobile application were seen as acceptable ways to support adherence.10

To improve adherence to therapy in the elderly, it is essential to explore and address a range of underlying challenges mentioned in figure 1. This requires a careful consideration of key questions (table 1) that form the foundation for determining appropriate and effective interventions.11

Table 1: Key questions determining appropriate and effective interventions11

| Factor | Key questions |

| Patient factors | How is the patient’s knowledge about his medicines and disease? Is the patient able to handle his own medication? Is the patient willing to take his medicine? |

| Medication factors | Does the medication need to be cut? Has the patient any chances to simplify the regimen? Are there any chances to simplify the regimen? |

| Healthcare providers factors | Is the healthcare team aware of the patient’s medication challenges at home? Has the patient communicated these concerns to the healthcare team, indicating a level of trust in them? |

| Healthcare system factors | Is the patient on polypharmacy? Is the shared patient record available to allow all HCP in need to check which medicine is the patient taking? Has the patient enough health literacy? |

| Socioeconomic factors | Is the patient able to care for himself? Does he have some family/friend’s support? |

Strategies to support medication adherence in the elderly

Medication non-adherence in older adults is a multifactorial challenge, often driven by polypharmacy, age-related physiological changes, cognitive decline, and system-level barrier. Hence, improving adherence in this population is unlikely to be resolved through simple or one-size-fits-all solutions.4

We have previously explored a range of adherence-promoting interventions. For details, please read our article: Interventions to tackle medication non-adherence and Community pharmacy interventions for outpatient medication adherence

Building upon that foundation, it becomes crucial to examine how these approaches can be adapted or tailored for older adults.

Types of behavioral and educational interventions

Healthy aging requires people to adopt and maintain beneficial behaviors in all stages of the life span. Supporting behavior change including via the motivation to make and maintain those changes, is therefore important for the promotion of healthy ageing.12

Behavioral interventions seek to influence individuals’ belief and attitude; in the context of adherence, they are designed to improve patients’ treatment-related behaviors. These interventions typically employ cognitive–behavioral strategies and therapies that address maladaptive emotions, behaviors, and thoughts, with the goal of encouraging healthier lifestyles and fostering more positive attitudes toward symptoms and treatment.12,13

Health/behavioral theories such as the Health Belief Model (HBM), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), Theory of planned behavior (TTB) and protection motivation theory (PMT) addressing cognitive factors like beliefs, motivation, and self-efficacy, are elaborated in our previous article.14

For a detailed exploration of these theories and how they inform effective behavioral interventions, read our article: “Methods of behavior change in medication non-adherence” and access masterclass Behavioral frameworks for understanding patient adherence

Common behavioral change intervention includes shaping, reminding (cues), or rewarding desired behavior (reinforcement):4,15,16

- Reminders and prompts: Alarm/beeper, telephone/email/mail reminders, visual cue systems (e.g., charts, medication lists), automated refill reminders

- Support tools: Calendars, daily diaries, large-print labels, compliance aids like multicompartment pillboxes or calendar packs

- Medication regimen simplification: Reducing dosing frequency or combining medications when appropriate

- Monitoring and feedback: Direct observation, inpatient programs of self‐administration of medications, or electronic monitoring with feedback loops

- Behavioral contracting: Verbal or written adherence agreements

- Skill-building interventions: Behavioral counseling, motivational interviews, supervised training, group education sessions, or peer support

- Follow-up systems: Home visits, scheduled clinic appointments, video, or teleconferencing-based check-ins

- Tailoring and routinization: Integrating medication-taking into daily routines

A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating medication adherence behavioral interventions for older adults with chronic illnesses found a moderate overall effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.500; 95% CI: 0.342–0.659), confirming the effectiveness of such strategies. Among the various interventions evaluated, the most effective were those that included implementation intention strategies (e.g., face-to-face meetings and telephone monitoring with personalized behavioral strategies) and a health belief model based educational programs. Face-to-face counseling emerged as a significantly effective method (Hedges’ g = 0.531; 95% CI: 0.186–0.877), whereas interventions delivered solely through education or telehealth counseling were less effective. These findings highlight the value of personalized behavioral change strategies and cognitive-behavioral approaches that engage older adults directly and meaningfully.17

Educational interventions involve: Delivery of medication-related information in a variety of formats (verbal, written, visual, audiovisual), provided by physicians, pharmacists, nurses, or allied health professionals. These can be offered individually or in groups (e.g., support groups, caregiver sessions) and may be reinforced by written materials or digital tools.4

The following components—drawn from frequently used interventions—can be tailored to the needs of elderly patients:18

- Promote rational, conservative prescribing: This includes reviewing and adjusting regimens to discontinue unnecessary medications, lowering doses where possible, simplifying regimens, and minimizing cost-sharing.

- Avoid the “prescribing cascade”: If new symptoms appear after starting a medication (e.g., pedal edema after initiating a calcium channel blocker), consider changing the original drug instead of prescribing additional medications to treat side effects

- Incorporate adherence measurement and risk assessment into clinical practice: With health information technologies, tracking refill histories and identifying adverse drug events is now feasible during routine visits. Tools can detect improper use (e.g., incorrect timing/dosing). Administer comprehensive geriatric assessments (CGA) to evaluate medical, psychosocial, functional, and environmental factors, and to guide treatment and follow-up planning.19

- Evaluate for age-related barriers: Be proactive in identifying common geriatric barriers such as financial constraints, use of multiple providers or pharmacies, cognitive decline, dexterity issues, difficulty swallowing, or sensory impairments. These should be directly addressed during consultations

- Consider beliefs and perceptions about medications: Older adults may have deeply rooted beliefs about medications—some may question their necessity or fear dependency. Open conversations around these beliefs are critical to building trust, ensuring acceptance, and developing personalized adherence strategies

Conclusion

As the global population continues to age, the burden of chronic disease and the complexity of medication management among older adults are set to rise sharply. Promoting medication adherence in this vulnerable group is both a public health imperative and a clinical challenge, requiring a nuanced, multifactorial approach.1,2 Adherence challenges in the elderly arise from both patient-specific limitations and external factors, such as healthcare system barriers and socioeconomic constraints.3,4 Tackling these requires more than just education—it demands tailored, multi-component interventions that consider the physiological, behavioral, and social realities of aging.3,4,13

Strategies such as medication simplification, behavioral support tools, personalized education, and ongoing patient-provider engagement can significantly enhance adherence.4 By understanding the unique needs of elderly patients and designing adaptable adherence strategies, health outcomes in an aging world can be improved.

“To care for those who once cared for us is one of the highest honors.”

— Tia Walker, The Inspired Caregiver