Policy and practice in healthcare systems to promote biosimilar use

- Biosimilars contribute towards the sustainability of the health system by offering alternatives to high-cost originator biologic products, however, there are numerous barriers to the uptake of biosimilars.1

- The lower-than-expected biosimilar uptake is due to lacunae in policies regulating and driving consumption like prescribing guidelines, pricing and procurement policies, and incentives for biosimilar use.1,2

- The key enablers to promote biosimilar sustainability are governmental regulatory policies, manufacturers, and prescribers.2

Biologics, biologicals, or biotherapeutics are biologically derived protein-based therapeutic agents that differ from chemically synthesized small-molecule drugs in terms of the molecular complexity and production process. Starting with insulin for diabetes treatment, biologicals have transformed the treatments for several common and/or serious diseases.3 Approximately 25% of all newly approved medicines and one in development are biologics showcasing their treatment promise across several indications.4

Due to the complex production process, biologics often carry a substantial price. Currently, biologics are prescribed for several critical medical conditions worldwide, and their consumption is expected to rise in the coming future.5 This poses a challenge to the financial sustainability of public-funded health systems and may render biologics unaffordable for patients in developing countries without state-funded medical treatment.6,7

What are biosimilars and can they enhance access to biologics?

Biosimilars are the non-innovator versions of the reference biologic drug for which the patent has expired. They are highly similar to their reference biologic with regard to efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity profile, yet less expensive.5,6

Therefore, they offer a more affordable option for biologics and healthy market competition leading to higher patient access and physician prescription choice to reimbursed biologic medicines.4,6,9 Biosimilars primarily contribute to enhancing accessibility through,8,9

- Enhancing the market competition such that multiple products are available in addition to the originator molecule.

- Price evolution resulting from the entry of biosimilars in the market due to the price reduction in originator molecule as well as lowered pricing of biosimilars.

- Increased volume of uptake pertains to additional consumption generated since the launch of the biosimilar.

- Alleviating budget pressures creating room for investment in novel treatments.

Regulatory policies for biosimilar uptake

The biosimilar development program primarily focuses on demonstrating similarity with the reference biologic in terms of molecular and functional attributes through extensive preclinical and clinical studies that establish no clinically meaningful differences based on structure, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, efficacy, and safety. Biosimilar approval follows the same quality and safety standards as that of originator molecule and any variability is kept within strict limits.2,10 The European Medical Agency (EMA) was the first to set up a regulatory framework for the marketing approval of biosimilars in 2006 and as of Aug 2020, has approved 72 biosimilars.2,6 Regulatory policies, similar to EMA, for biosimilar marketing approval have since been formulated in other countries including emerging markets.2

However, the marketing approval alone doesn’t ensure biosimilar uptake. It rather depends on policies encouraging/discouraging biosimilar usage, which vary substantially among countries both in mature and emerging markets.2 Some of the policies that influence biosimilar uptake are:

- Biosimilar prescription guidelines: Unambiguous guidelines for biosimilars as well as guidance on biosimilar switching enable physicians in treatment decision-making. A key prescribing policy is to prescribe using the non-propriety name rather than the trade name of a medicine. However, policies in certain countries do not explicitly mention biosimilars in the prescribing policies.6

- Rules for biosimilar switching: The novelty of biosimilars and limited data have been concerns about switching between originator and biosimilar. In European countries switching is recommended at physician’s discretion, but should be done with patients consent and no automatic substitution.4

- Pharmacy substitution: Substitution at the pharmacy level is a potent mechanism for utilizing economical medications. It is defined as “a practice of dispensing one medicine instead of another equivalent and interchangeable medicine at the pharmacy level without consulting the prescriber”.5,6 Automatic pharmacy substitutions are prohibited for biosimilars in most countries.4

- Biosimilar reimbursements: Difficulty and delay in reimbursements for biosimilar or burden of higher out-of-pocket costs is a major barrier to biosimilar uptake.5,6

- Pricing policies: These policies allow linking and capping the maximum price for the biosimilar to a certain percentage lower than its respective originator. Pricing of any subsequent biosimilars can also be linked to the existing biosimilars resulting in further lowering of prices and market competition. Additionally, these policies can have provisions for influencing the cost of reference drugs upon the introduction of biosimilars in the market.6,9

- Biosimilar procurement practice: Procurement practices like national vs. regional or hospital-level tenders, length of contracts, and single vs. multiple winners impact the competition and long-term savings as well as supply chains.6,9

- Physician education: The policies also must consider the educational needs of physicians to generate awareness about biosimilars due to their novelty and uniqueness.5

- Incentives for biosimilar use: These include economic incentives for physicians to encourage biosimilar uptake. Countries may mandate a predefined target share for prescribing biosimilars that healthcare practitioners need to achieve while prescribing.5,6

While Europe leads in biosimilar consumption contributing to around 60% of the global market share, the policies for biosimilar use are not uniform across member states.4,6 A detailed country-specific biosimilar policy framework employed in different European countries is listed in Table 1 providing a glimpse of on-ground facilitators and barriers to biosimilar uptake.

Table 1: Key biosimilar policies implemented in Europe.

| Country | Prescribing guidelines | Biosimilar switching policy | Substitution policy | Pricing policy | Reimbursement | Incentives for biosimilar |

| Denmark | Specific recommendations for a few biosimilars | Prescription by brand; INN prescription not permitted | Not permitted | 20–30% originator discount upon biosimilar entry; No mandatory discounts for biosimilars | Allowed for recommended drugs; hospital budgets are capped | No economic incentives for patients or prescribing targets for physician |

| France | No specific guidelines | Prescription by INN; Switching allowed with patient’s consent | Allowed with patient and physician consent | No mandatory discounts either on originator or biosimilar | Expensive drugs covered via social security funds | No economic incentives for patients or prescribing targets for physician |

| Germany | No specific guidelines | INN prescription not mandated; switching at physician’s discretion | Not permitted | Marginal originator discounts on LOE; No special discounts on biosimilars | Expensive drugs covered via insurance funds | Some incentives to patients; prescribing targets for physician |

| Hungary | No specific guidelines | Switching at the physician’s discretion | Not permitted | 30% discount on the first and a 10% discount with subsequent biosimilar entry | Simplified reimbursement process for biosimilars | Prescribing targets for physician |

| Italy | No specific guidelines | Switching at the physician’s discretion | Permitted only with physicians’ notification | No mandatory discounts on originators with biosimilar entry | Full reimbursement from national/regional taxation funds | No economic incentives for patients or prescribing targets for physician |

| Norway | Provides guidance for biosimilar use and switching | INN prescription encouraged, switching at physician’s discretion | Not permitted | No mandatory price reduction for the originator | Fully reimbursed | No economic incentives for patients or prescribing targets for physician |

| Sweden | No specific guidelines | Switching at the physician’s discretion | Not permitted | No mandatory price reduction for the originator | Full reimbursement | No significant incentives for patients or prescription quotas for physicians |

| Poland | No specific guidelines | switching at the physician’s discretion | Not permitted | 25% reduction in originator price at LOE | Full reimbursement | No significant incentives for patients or prescription quotas for physicians |

| Romania | No specific guidelines | Allowed at physician’s discretion | Not permitted | 20% reduction in originator price at LOE; Biosimilar 20% lower than originator | Reimbursement policies encourage the originator use | No significant incentives for patients or prescription quotas for physicians |

| Spain | No specific guidelines or guidance | Allowed at physician’s discretion | Not permitted | Biosimilar 25-30% lower than originator | Full reimbursement | No significant incentives for patients or prescription quotas for physicians |

| United Kingdom | Same guidance as that of originator | Allowed at physician’s discretion | Not permitted | No special pricing schemes for biosimilars or price reductions for originator | Full reimbursement | No significant incentives for patients or prescription quotas for physicians |

Data sourced from country Scorecards for Biosimilar Sustainability (IQVIA report), 20209

LOE: Loss of exclusivity; INN: International non-proprietary name

Barriers to biosimilar access in emerging markets:

Emerging markets offer tremendous opportunities for biosimilars with an increased prevalence of biologic-treatable chronic diseases and an insufficient public infrastructure to afford high-cost treatments.2 However, they have failed to penetrate these markets due to the following unique attributes:2,12

- Weak regulatory frameworks: Lack of guidelines for biosimilars and guidance on switching results in reluctance to prescribe biosimilars by physicians. Many emerging markets also lack pharmacovigilance guidelines which are crucial to ensure biosimilar safety and efficacy.

- Dependence on imports: Due to technical challenges and a lack of resources to locally manufacture biosimilars, many countries are dependent on imports which may constrain the supply chains.

- Lack of approved reference product: Regulatory approval for biosimilars in many countries requires establishing comparative efficacy with a locally approved reference product, which may not be the case for the given biosimilar hindering its approval.

- Low awareness: Low awareness about biosimilars and lack of educational programs to change the perception of physicians and patients deters biosimilar uptake.

- Lack of pricing policies: Pricing policies that encourage the uptake of biosimilars as seen in Europe do not exist in emerging markets.

Enablers of biosimilar uptake

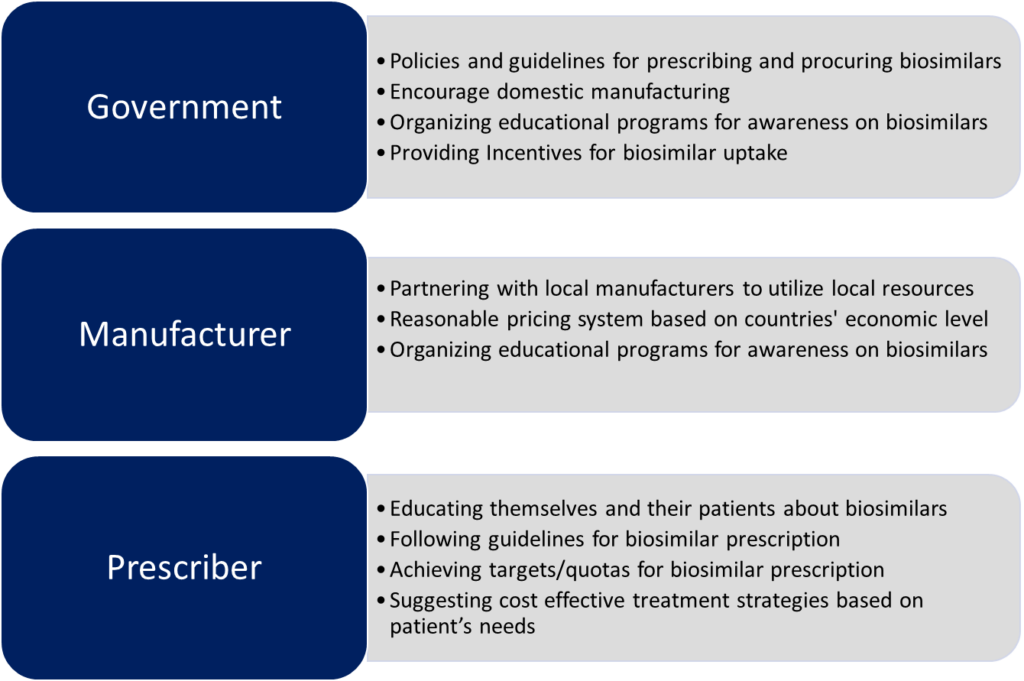

The key stakeholders that can influence biosimilar uptake in any country are government, manufactures and prescribers. Government regulatory bodies create policy for the uptake and generate awareness, while manufactures and prescribers are key for creating sustainable biosimilar landscape and driving consumption as shown in figure 1.2

Figure 1: Key stakeholders and enabling strategies for promoting biosimilar uptake.

The figure is for illustration purposes only and is adapted from Chabbra et al., 20222

A Delphi consensus panel from Europe agreed that the key drivers and risks to biosimilar sustainability are:11

- Market competition which is more effective than price regulation

- Incentives to industry for investment in biosimilar development

- Government and pricing bodies need to drive the incentives

- Avoiding monopoly and disruptions in the procurement process

- Biosimilar procurement policies should have a consistent approach with a common guiding principle taking into account the views of all stakeholders

Examples of successful implementation of policies for biosimilars

Implementation of the policies that encourage biosimilar uptake has led to the approval of the highest number of biosimilars in Europe and their higher utilization. The use of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) approach by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in United Kingdom has led it to instruct rheumatologists to prescribe the least expensive option.

The quota system for biosimilars has driven their prescription in Germany and Belgium to up to 40%. Strong financial incentives to Health Systems for switching to biosimilars in Norway have resulted in an increase in the market share of epoetin and filgrastim biosimilars to 80%.13

Policies encouraging biosimilar uptake in emerging economies may play an important role in enhancing patient access as these countries spend disproportionately more on out-of-pocket costs in healthcare. India and South Korea are the flagbearers of encouraging local manufacturing. They can now penetrate the global market through strategic alliances with established biosimilar manufacturers. India has already approved over 100 locally manufactured biosimilars and is now also penetrating other markets via their partnership with international players.2

Conclusion

Biosimilars have the potential to enhance patient access to biologics by increasing competition, cost reduction, and broadening the choice of medications. This can positively impact the cost-related non-adherence to biologics. With the increased use of biologicals for various indications, it is pertinent to lay down regulatory and pricing policies that allow a level playing field to foster competition as seen in Europe that could be adopted and adapted in other regions as well. Access to educational programs that create awareness about biosimilars and the regional regulatory/prescribing policies can enable physicians in decision-making and driving consumption.4

“A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking real money”

~ Everett Dirksen, US Ex-Congressman