Understanding Patient Attitudes: The Health Belief Model

- The Health Belief Model (HBM) is a model to help understand what patients believe about their health

- The HBM can be used to identify detrimental patient behaviors caused by a poor understanding of a condition or treatment

- The HBM can be used to structure interactions with patients to enhance their understanding of treatment and lifestyle recommendations

How do people think about their health?

Why do people engage in behavior they know is detrimental to their health? With the emergence of modern public healthcare policy after World War II, healthcare professionals began to examine new ways to understand patient behavior. Queries into patient behavior are at the center of the first systematic, theory-based health behavior research and the development of the Health Belief Model (HBM) in the early 1950s.

The two key components of any individual’s understanding of their health condition are perceptions of risks and their susceptibility to the consequences

The HBM premise

The Health Belief Model grew out of the work of early social psychology pioneers, such as Kurt Lewin, who wanted to understand how best to guide the new domain of public health policy and communications. Early versions of the HBM, based on research investigating attitudes towards health screening, appeared in the 1950s.1 As it is typically used today, the HBM was formalized by Rosenstock in 1974,2 and it is the foundation of most models for understanding human health behavior.

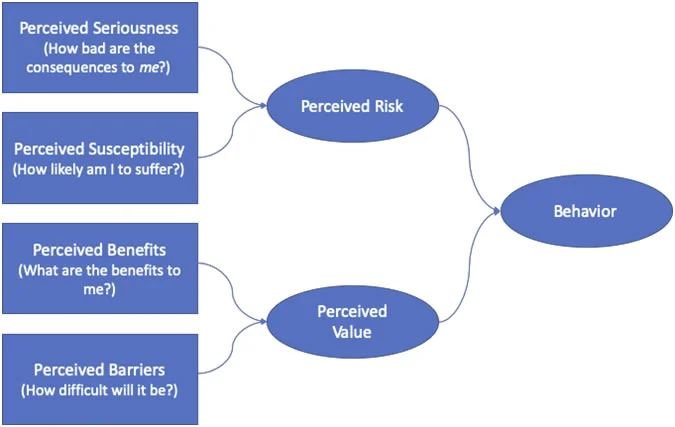

The HBM characterizes health decision making as cost-benefit analyses, or in the language of social science, an “expectancy-value” model. That is, people consider the value of behavioral change in terms of the perceived benefit or risk reduction and compare that to the perceived costs, i.e., effort, time, money, and other negative impacts on their life. If the perceived benefits of adopting a new behavior outweigh the costs, then the expected value is sufficient to prompt action or make a behavioral change, e.g. submit to x-ray screening, quit smoking, or adhere to a treatment plan.

While the rational decision making approach of the HBM makes intuitive sense, developers went further and broke it down in terms of the effects of health beliefs on patient behavior; they determined that there are two separate considerations: those concerning the condition or disease and those concerning treatments.

Part 1: Understanding the condition

According to the HBM, the two key components of an individual’s understanding of their condition are their perceptions of the seriousness of their condition’s consequences and their susceptibility to those consequences. For example, when considering whether to quit, a person who smokes will first decide how serious the consequences of smoking are, e.g. lung cancer or premature death, and then determine how likely it is that the consequences will manifest.

It is important to remember that the key point here is the patient’s perception of both seriousness and susceptibility – not necessarily what clinical and epidemiologic studies might suggest. For example, while premature death is objectively quite serious, not everyone will be motivated to modify their behavior by a fear of premature death. To a 30-year-old who smokes, the possibility of dying at age 75 instead of 82 may not seem particularly serious, and if they have a relative who smoked their whole life and died at 90 of other causes, they may minimize or dismiss their own susceptibility to premature death. (This is an example of the availability heuristic we discussed in the article, Heuristics and decision-making: what are the effects on adherence for patients with vertigo? ). Taken together, these considerations of seriousness and susceptibility form the patient’s perceived risks of their condition or of continuing with current behaviors, e.g. smoking, not getting tested, not taking medication, etc.

Part 2: Understanding the treatment

The other half of the equation is the patient’s understanding of the proposed behavior changes needed to manage their condition. This can be further broken down into perceived barriers to the new behavior and the treatment’s perceived benefits.

Before quitting tobacco, the same 30-year-old will have to determine whether quitting will reduce the possibility of premature death or if that benefit will no longer be available to them even if they now modify their behavior. And in terms of barriers, the perception that it is difficult to quit tobacco is ubiquitous, and there may be other fears, like weight gain, preventing a change in behavior.

The HBM illustrated

The patient’s perceptions and beliefs combined will determine whether there is value in changing the current behavior in favor of suggested behaviors or treatments.

The model therefore looks like this:

The HBM and adherence in vertigo

The Health Belief model has been amply studied in terms of the behavior of patients with chronic conditions, predicting patient behavior and providing guidance for effective patient education. No studies exist examining its application for patients suffering from vertigo, but a number of pathologies that have been closely studied present similar behavioral dynamics. For example, as discussed in previous articles, chronic pain, mild epilepsy, and mild multiple sclerosis are all conditions in which the symptoms, while troublesome, are episodic in nature. The HBM has proven its value in the context of these conditions in assisting healthcare professionals to understand patient behavior and effectively guide behavioral changes.3, 4

The HBM has been especially successful within neurology in helping patients understand their conditions and their treatments and to modify their behavior, and it has also proven useful in a variety of fields, both as a means of structuring interventions and measuring success.

Influencing the patient using the HBM

The HBM allows healthcare professionals to access and assess the patient’s potential behavior by breaking down their beliefs. Following the HBM, a healthcare provider should:

- Assess the patient’s understanding of the potential consequences of their disease.

- Make sure the patient knows that:

- they are susceptible to those consequences, and

- that they have a degree of control over the outcome if they follow the treatment.

- Assess the patient’s understanding of the benefits of the treatment to ensure they fully understand those benefits.

- Make sure that the patient has a realistic understanding of side effects to ensure that if side effects manifest, they do not undermine the perceived value of the behavior change.

Example: Using the Health Belief Model

Consider the case of a 30-year-old patient suffering from vertigo. The sporadic nature of the condition lowers the patient’s perception of risk, in terms of both seriousness and susceptibility, and because of the patient’s relative youth, there is an additional barrier created by the difficulty of accepting the chronic condition identity. The persistence of occasional episodes despite adherence to treatment leads the patient to dismiss the positive effects of the medication and undervalue the benefit of following their treatment plan. This results in non-adherence.

This is a common phenomenon and may be seen in other neurological conditions, such as mild relapse-remitting multiple sclerosis or mild epilepsy.

A prescriber’s approach that significantly influences a patient’s understanding can have a dramatic effect on behaviors. By asking careful questions, such as those outlined above, a provider can ensure that the patient has the understanding needed to modify their behavior and adhere to treatment. Rudimentary explanations of the disease or treatment, or worse, an assumption that the patient will simply do as they are told, reduce the likelihood that the patient will engage in the desired behavior. Incorporating the HBM can help providers effectively structure the crucial conversations that must take place to help patients adopt healthy behaviors and adhere to treatment.

Final thoughts

The Health Belief Model does have limitations. It assumes patients will engage in rational behavior, which is not always the case. It also does not adequately address the fact that many of the behavior changes in a treatment plan, like medication adherence, diet, and exercise, are not one-time decisions, but rather a series of daily decisions that must be made over an extended period of time, often for many years.

The HBM is an excellent starting point, however, newer behavioral models have emerged since the development of the HBM to address the complicated structure of human cognition to assist patients with treatment adherence.5 As part of its limitations, the HBM gives only tangential consideration to the patient’s assessment of their ability to change behavior, otherwise known as self-efficacy. Self-efficacy and more detailed psychological considerations addressing the question of overall health motivation have led to the elaboration of protection-motivation theory,6 and paved the way for additional frameworks which will be presented in future articles.