Understanding the emotional impact of a lung cancer diagnosis

Lung cancer is not only the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, but also one of the most emotionally devastating diagnoses a patient can receive.1 When a patient hears “you have lung cancer,” they embark on an intense emotional journey that can profoundly affect their mental health, treatment adherence, and quality of life.

As a healthcare professional (HCP), understanding this journey, and leveraging behavioral science techniques to guide patients through it, is crucial. This comprehensive guide provides evidence-based insights into the emotional impact of a lung cancer diagnosis and practical strategies for HCPs to support patients, grounded in empathy and robust science.

A new lung cancer diagnosis often triggers a cascade of overwhelming emotions. Many patients experience an initial period of shock or denial as they struggle to process the bad news.2 Fear and anxiety are common, stemming from uncertainty about prognosis, treatment, and mortality.3 In fact, 40-50% of lung cancer patients have reported to be suffering from significant psychological distress around the time of diagnosis.4-6 This distress can manifest as acute anxiety, panic, or profound sadness,4,6 and it affects not only patients but also their loved ones.7,8 There may also be feelings of guilt or shame, especially in patients with a history of smoking, due to the stigma associated with lung cancer.9 All these emotions are “too rarely spoken about” in clinical encounters, leading many patients to carry their emotional burden in silence.

Notably, studies have identified depression and anxiety as particularly prevalent among patients with lung cancer. Depression is the most common psychological disorder in this population, with a Chinese study reporting that up to 57% of patients may develop clinical depression over the course of the illness.10 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has even labelled psychological distress the “sixth vital sign” in cancer care, underscoring that emotional well-being should be monitored as routinely as blood pressure or pain.11 Importantly, high levels of distress are linked to worse quality of life and can negatively impact physical symptoms.12 For example, greater pain, fatigue, and insomnia correlate with more severe emotional distress, creating a vicious cycle.13 Untreated depression or anxiety may also affect outcomes; research shows that psychological distress (e.g. depression) can be a prognostic indicator of poorer survival in cancer patients.14

Every patient’s emotional journey is unique, but certain common emotional responses tend to arise with a lung cancer diagnosis:15

- 1. Denial

Denial is frequently the initial reaction to a cancer diagnosis. Patients may exhibit avoidance, confusion, or disbelief, often accompanied by fear. Common expressions include, “This can’t be happening to me,” or “There must be a mistake.” This stage serves as a psychological buffer, allowing individuals time to process overwhelming information. HCPs should approach this phase with patience and clarity, offering reassurance and factual information without overwhelming the patient.15 - 2. Anger

As reality begins to set in, patients may transition into anger. This stage is characterized by frustration, irritability, and anxiety. Thoughts such as “Why me?” or “This isn’t fair” are typical and may be directed toward themselves, loved ones, or even medical professionals. It is crucial for HCPs to acknowledge these emotions without judgment, maintain open communication, and provide a safe space for patients to express their feelings.15 - 3. Bargaining

In an attempt to regain control, patients may enter the bargaining phase. This can manifest as seeking second opinions, questioning the diagnosis, or expressing hope for alternative outcomes. Statements like, “There must be something else we can try,” or “Please check again,” are common. While this stage may not yield clinical solutions, it reflects the patient’s need for hope and agency. HCPs should validate these concerns while guiding patients toward evidence-based options.15 - 4. Depression

As the reality of the diagnosis becomes more concrete, patients may experience emotional withdrawal, sadness, and hopelessness. Feelings of helplessness and despair can emerge: “What’s the point in fighting?” or “I’m going to die anyway…. This stage requires sensitive intervention. HCPs should monitor for signs of clinical depression and consider involving mental health professionals to support the patient’s psychological well-being.15 - 5. Acceptance

Acceptance does not imply happiness but rather a recognition of the situation and a willingness to move forward. Patients may express sentiments such as, “I’m going to face this head-on,” or “This will be difficult, but I’m ready to try.” At this stage, patients are often more receptive to treatment plans and support systems. HCPs can play a pivotal role in fostering resilience and helping patients find meaning and purpose in their journey.15

It’s important to remember that these emotions are not experienced in neat “stages.” Patients can cycle through feelings or have many emotions at once. As an HCP, validating these feelings and normalizing them can help patients feel understood rather than “weak” or “crazy.” For example, simply saying, “It’s completely understandable to feel afraid or overwhelmed” can provide reassurance. Early integration of psychosocial support is key: patients who receive mental health support from the point of diagnosis cope better and have improved outcomes.16

The HCP’s Role: Communication, Empathy, and Support

Healthcare professionals play a pivotal role in guiding patients through this emotional journey. From the moment of delivering the diagnosis onward, how information is communicated can significantly influence a patient’s psychological adjustment. Effective clinician–patient communication is considered a core element of patient-centered oncology care.17 In fact, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) convened an expert panel to develop guidelines on patient-clinician communication, underscoring the need for strong provider-patient relationships built on empathy, honesty, and trust.18

The guidelines are available here: Patient-Clinician Communication – American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline

When discussing a lung cancer diagnosis, compassionate honesty is paramount. Patients have a right to know the truth about their condition, but blunt delivery can be devastating.19 The goal is to “preserve their hope while at the same time giving them accurate information,” as Dr. Timothy Gilligan (co-chair of the ASCO communication guideline panel) advises.20 In practice, this means balancing realism with empathy. Healthcare providers should work with patients to define care goals, ensuring a clear understanding of prognosis and therapeutic choices.20 Conveying that you, as the HCP, will continue to support them no matter what can help sustain hope.

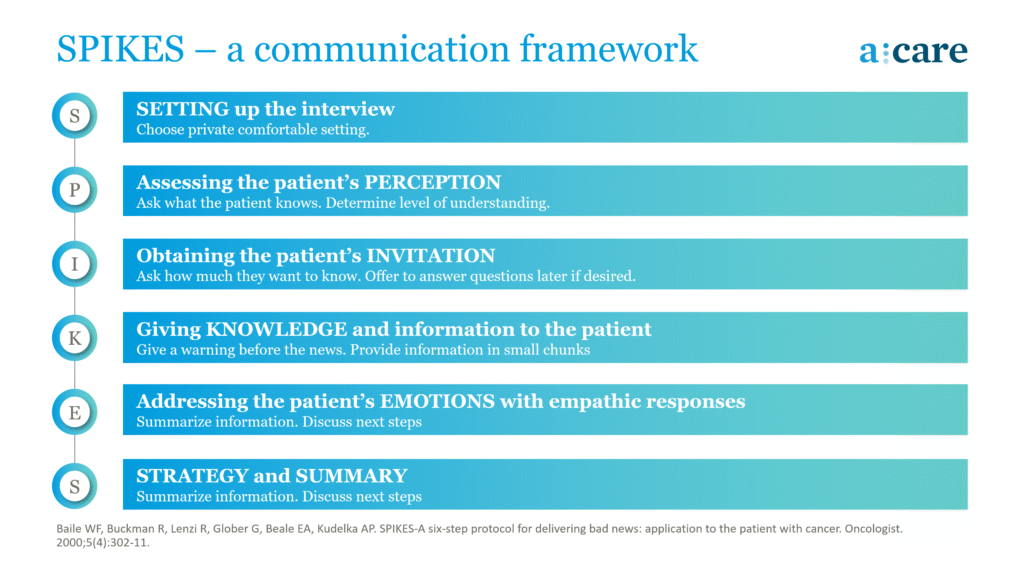

Use proven communication frameworks for breaking bad news, such as the SPIKES – a stepwise framework for difficult discussions. Each letter represents a phase in the six-step sequence. S stands for setting, P for perception, I for invitation, K for knowledge, E for empathy, and S for summarize or strategize, to ensure you cover key steps in an empathetic manner.21 Briefly, SPIKES involves:21

- Setting up a private, comfortable environment and ensuring adequate time for discussion.

- Assessing the patient’s Perception of their situation (what do they already understand?).

- Obtaining the patient’s Invitation to share information (how much detail do they want?).

- Sharing Knowledge about the diagnosis and next steps in clear, jargon-free language.

- Addressing the patient’s Emotions with empathic responses – acknowledge and name their feelings (“I can see this news is very upsetting”).

- Summarizing and outlining next Steps/Strategy, so the patient knows there is a plan moving forward.

Further reading: SPIKES – A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer

Throughout this conversation, empathetic body language and active listening are essential. Sit down at eye level with the patient, offer tissues if they become tearful, and allow silences, oftentimes, “when the patient is talking, you [the physician] shut up”, as Dr. Robert Buckman famously quipped.22 Avoid interrupting; use brief verbal cues or repetition of the patient’s words to show you are truly listening. These behaviors, though simple, powerfully convey respect and caring. Remember that patients may not recall much of the medical details you explain (due to shock), but they will vividly remember your demeanor and empathy.

Building Trust and Encouraging Openness

From day one, work to establish a trusting relationship with the patient. Make it clear that you and your multidisciplinary team are there to support all aspects of their well-being, not just the tumor. Encourage patients to voice their concerns and questions. ASCO guidelines recommend that clinicians actively partner with patients by inviting questions and concerns, and by involving patients in decision-making at every visit.18 This collaboration makes patients feel heard and respected, which in turn reduces anxiety. Simple practices like asking “What worries you most right now?” or “Is there anything specific you’d like to discuss today?” can open the door for patients to express fears that they might otherwise keep hidden (such as fear of treatment costs, or how to tell their family). Indeed, discussing practical worries like the cost of care is also important:18 many patients have anxiety about finances, and addressing these directly (or referring to a social worker) can relieve one source of stress.

Crucially, address stigma and guilt head-on. If a patient feels guilty (“I smoked for 30 years; I feel this is my fault”), respond with compassion.23 You might say, “We can’t change the past, but what matters now is that we focus on your treatment and support. No one deserves cancer. I’m here to help you going forward.” Emphasize that many people with lung cancer never smoked, and even for smokers, tobacco is one risk factor among many. The goal is to alleviate self-blame so that the patient can engage with care rather than hiding in shame. Research shows that stigma and negative self-appraisal worsen psychological distress and quality of life,24 so tackling these feelings is a therapeutic intervention in itself.

Practical Communication Tips for HCPs

To summarize, here are some practical communication strategies for oncology professionals working with lung cancer patients:25

- Create a Safe Space:25 Deliver news in a private, quiet setting with no rush. Turn off phones/pagers if possible. Starting with “I’m afraid I have difficult news” can prepare the patient for bad news while conveying empathy from the outset.

- Use Clear, Honest Language:25 Avoid euphemisms or excessive medical jargon. Check understanding frequently (e.g., “Let me pause here – what have you understood so far?”).

- Express Empathy Verbally and Nonverbally:17,26 Say things like “I know this is a lot to take in” or “I can imagine this feels overwhelming.” Use caring tone and eye contact (but be sensitive – e.g., a patient in tears might prefer a moment without eye contact). Small gestures of warmth and patience go a long way.

- Invite Questions and Revisit Information:18 Encourage the patient (and their family, if present) to ask any questions now or later. Acknowledge that they might think of questions after they go home and provide a way to contact you or a nurse. Reassure them that it’s normal to not absorb everything at once.

- Provide Hope within Realism:28 Even if the prognosis is guarded, highlight treatable aspects: “We have treatments that can help control the cancer and certainly we will do everything to manage any symptoms you have.” Emphasize your commitment: “We will be with you through this.” This helps patients feel they are not alone on this journey.

- Plan the Next Step: Before ending the conversation, outline what will happen next (additional tests, meeting the surgeon or oncologist, starting therapy, referral to support services, etc.). A concrete plan can reduce anxiety of the unknown.29

A lung cancer diagnosis is not just a medical event. It is a profound emotional upheaval that reverberates through every aspect of a patient’s life. The psychological toll, often underestimated, can be as debilitating as the physical symptoms. From denial and anger to depression and eventual acceptance, patients navigate a complex emotional landscape that demands empathy, patience, and support.

Healthcare professionals are uniquely positioned to ease this journey. By recognizing emotional distress as a critical component of cancer care, on par with physical symptoms, they can foster a more holistic, compassionate approach. Effective communication, early psychosocial intervention, and a commitment to ongoing emotional support are not optional; they are essential. When patients feel heard, understood, and supported, they are better equipped to face the challenges ahead, engage with treatment, and maintain hope—even in the face of uncertainty.

Ultimately, acknowledging and addressing the emotional impact of lung cancer is not just good practice. It is humane care.

This article was written with the assistance of generative AI technology and reviewed for accuracy.

Common reactions include shock, fear, anxiety about the future, sadness or depression, anger, and sometimes guilt (especially if smoking is a factor).2-6 Acknowledge these feelings to the patient as normal responses to a life-changing diagnosis. Let them know that distress is very common (around half of lung cancer patients experience significant anxiety or depression) and that help is available. For example, you might say, “Many people feel overwhelmed and frightened when they’re diagnosed. You’re not alone in feeling this way. We have resources to support you emotionally, just as we will medically.” Normalizing emotions helps patients feel less isolated and more willing to accept support.

Use a structured approach like the SPIKES protocol to break bad news with empathy.21 Ensure you’re in a private, quiet setting and allocate enough time. Start gently (e.g., “I’m afraid I have difficult news”), then convey the diagnosis in clear terms, avoiding medical jargon. After sharing the news, pause to allow the patient to process and express emotion. Respond with empathy: say “I know this is not what you wanted to hear, I’m so sorry you have to go through this.” Answer questions truthfully but tactfully, and offer hope by explaining that treatments and support exist. End by outlining next steps (for instance, further tests or a treatment plan) so the patient isn’t left in limbo. This approach preserves trust and hope while maintaining honesty.18

First, directly address the stigma. Reassure your patient that they do not deserve blame for their illness. Explain that while smoking is one risk factor, many smokers never develop lung cancer and many lung cancer patients never smoked: the disease is biologically complex. Emphasize that now is the time to focus on treatment and support, not past behaviors. Use compassionate language: “I hear you feeling guilty, but I want you to know that you’re not to blame for this. We have many patients with lung cancer who struggle with these feelings. Our job is to help you get the best care, not to judge how you got here.” Also, avoid any inadvertent language of blame in your own communication (for example, instead of pointedly asking “How long did you smoke?” you might ask more neutrally about medical history). Encourage patients to involve family or counselor discussions if guilt persists. Reducing stigma and self-blame can improve their mental health and make them more likely to seek the help they need.

Healthcare professionals play a critical role in supporting patients emotionally. Key strategies include:

- Communicating with empathy and clarity during diagnosis and treatment discussions

- Normalizing emotional responses and validating patient feelings

- Monitoring for signs of psychological distress, such as depression or anxiety

- Referring patients to mental health services early in the care process

- Maintaining a supportive presence, reinforcing that the patient is not alone

Following guidelines from organizations like ASCO, clinicians can foster trust and resilience, improving both emotional and clinical outcomes.

While many patients experience emotions similar to the stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance) these stages are not linear or universal. Patients may move back and forth between emotions or experience several simultaneously. Understanding this variability helps healthcare providers respond with flexibility and compassion.