Digital nudges and medication adherence

- Digital nudges, rooted in behavioral science, can subtly guide patients toward better medication adherence without removing their freedom of choice.1, 2

- Nudge effectiveness depends on context and personalization—a successful design should define clear goals, understand the users, design the nudges as per user choices and test nudges thoroughly. One-size-fits-all nudges risk being ineffective or ignored.3

- Mobile apps, SMS reminders, electronic monitoring devices (EMDs) etc have shown promise for improvements in medication adherence across diverse therapeutic area.4

Decoding the concept of nudges

“People are not always rationale. Nudges help them make better choices without taking away their freedom to choose”

The concept of nudging originated from behavioral economics discipline and was popularized by Thaler and Sunstein. It is built two core principles: choice architecture and libertarian paternalism.2,5

Choice architecture refers to the deliberate design of environment in which individuals make decisions. Specific features of this environment that influence individual decision-making in a predictable way without restricting any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. These small design features that guide individual toward better decisions are known as nudges.2,5

Nudging is grounded in the understanding that when faced with uncertainty or complex decisions, people often rely on heuristics or mental shortcuts, which can lead to cognitive biases and suboptimal outcomes. For example, decision-makers including clinicians may show a status quo bias, preferring to stick with default options even when alternatives may yield better results. Leveraging this tendency, opt-out default settings can serve as powerful nudges, encouraging behavior that aligns with guidelines, such as adhering to care standards in clinical practice, while still preserving individual autonomy.1

Libertarian paternalism complements this concept by promoting intervention that aim to improve individual outcomes while preserving “freedom of choice”. In essence, nudging doesn’t force decisions, it makes the preferred choice easier to follow.5

For more details on heuristics, please read our article: Heuristics and decision-making: what are the effects on adherence for patients with neurological disorders?

From nudges to digital nudges

Life is full of choices—many made in digital environments. From shopping online to using e-government services, decisions are often shaped by how options are presented, not just by what they are.3

When applied in digital settings, this idea becomes what we know as “digital nudging”. Weinmann et al. define digital nudging as “the use of user-interface design elements to guide people’s behavior in digital choice environments”.3,5 Expanding on this, Mirsch et al. describe digital nudges as “relatively minor changes to decision environments” within software applications. For instance, a reminder pop-up, a default setting, or visual cue in a mobile app are all examples of digital nudges. Meske and Potthoff build on Weinmann et al.’s definition by emphasizing free decision-making and expanding nudging beyond user interface (UI) changes to include the form and content of information. They describe digital nudging as a subtle use of design, information, and interaction elements to guide behavior without limiting choice.5

A classic example of a nudge in healthcare is the use of pre-selected default options in an electronic prescribing system. This small design tweak: a nudge—can reduce inappropriate prescriptions of antibiotics without removing the clinician’s ability to override the default.1

Categories of digital nudges and their information environment

Understanding an environment is key: individual must learn about its structure and characteristics to make sound decisions. This understanding is also essential when evaluating the success—or failure—of nudging interventions. The effectiveness of a nudge can depend on the type of environment in which it is deployed.

Environments can generally be categorized into two types:6

- Kind environments: Offer accurate, timely, and direct feedback; relatively uninformed decision makers can easily adapt by trial-and-error behavior

- Wicked environments: Characterized by complex, opaque, and shifting variables; feedback is often delayed, misleading, or confounded by external factors; can lead to false beliefs, poor judgments, and misguided actions.

Digital nudges can be categorized into two distinct types:6

- Behavioral nudges: instigate a specific behavior or action, focuses on changing user behavior directly. They include strategies like setting default choices (sets the preferred option as the default), reducing errors through prompts, provide feedback to decision makers on consequences of their behaviors, and structuring complex choices.

- Informative nudges: designed to enhance user awareness by increasing transparency about environmental variables and decision-making contexts. This includes increasing salience of information or incentives, which makes options more noticeable using text, color, animation, or alerts; and understanding mapping, which simplifies the relationship between choices and outcomes using flowcharts or decision trees summarizing clinical guidelines.

To know more about why nudging is needed? and different techniques used to instigate change in behavior, read our articles: “Nudging” patients towards better adherence to improve outcomes and Behavioral approaches to changing adherence

Designing a digital nudge

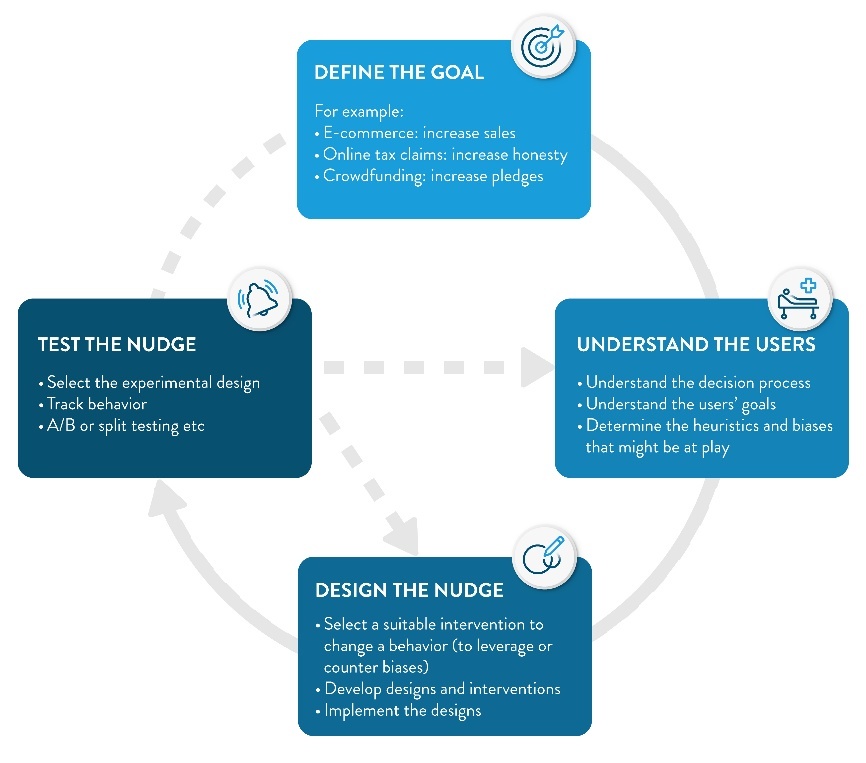

The process of designing digital nudges follows a cycle, starting with defining the goal and progressing through user understanding, design, and testing.3

Figure 1: Designing digital nudges follows a cycle3

Bridging into medication adherence

Digital nudges are increasingly being used to tackle real-world challenges in healthcare—especially medication non-adherence. Despite medical advice, many patients miss doses or stop treatment due to busy schedule, their personal belief, forgetfulness etc. Digital interventions, delivered via mobile apps, SMS-based tools, websites, web applications, or electronic adherence monitoring devices—offer multi-functional capabilities, including communication, data collection, and interactive user experiences. These features can be used to provide timely reminders, simplified instructions, or default refill settings, guiding patients toward better adherence without taking away their freedom to choose.4

The clinical effectiveness of these digital interventions has been evaluated across a variety of settings and patient populations. A Cochrane review analyzing 40 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 15,207) evaluated the impact of digital interventions on medication adherence in asthma. Most studies focused on adherence as the primary outcome, with additional data on asthma control, quality of life, and healthcare utilization. Meta-analysis revealed that digital interventions may improve adherence by an average of 14.66 percentage points (95% CI: 7.74–21.57). The effect was more pronounced in patients with poor baseline adherence. Among intervention types, electronic monitoring devices showed the highest improvement (+23 percentage points), followed by short message services (+12 percentage points) compared to control. These findings support the clinical value of digital tools in improving long-term medication-taking behavior.4

Another Cochrane review involving over 25,633 participants across 14 RCTs assessed the effectiveness of interventions delivered by mobile phone to improve adherence to medication prescribed for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adults. These ranged from SMS-only reminders to comprehensive approaches that included face-to-face counselling, electronic pillboxes, written materials, and home monitoring devices. Across five trials (5,441 participants), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reductions ranged from −5.30 mg/dL (95% CI: −8.30 to −2.30) to −9.20 mg/dL (95% CI: −17.70 to −0.70) in two studies, while others showed minimal or no effect. Among 13 studies (25,166 participants) measuring systolic blood pressure, effects varied widely—from a large reduction of −12.45 mmHg (95% CI: −15.02 to −9.88) to a small increase of 2.80 mmHg (95% CI: 0.30 to 5.30). The systolic and diastolic blood pressure benefits were observed in interventions combining self-monitoring with mobile phone-based telemedicine, whereas SMS-only interventions showed minimal improvements (e.g., −1.55 mmHg; 95% CI: −3.36 to 0.25). These findings further underscore the role of mobile-based digital strategies in improving adherence to medication prescribed for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.7

Pilot studies have also demonstrated the feasibility of using behavioral text message nudges to improve medication refills. In one such study, patients with a ≥7-day gap in cardiovascular medication adherence were identified via electronic health record pharmacy data and sent automated, theory-informed text messages via third-party software platform. Patients receiving these nudges had higher refill rates (30.6% vs 18.0% for at least one medication; 17.8% vs 10.0% for all medications). The system was successfully automated and scaled without technical issues, showing that such an approach is operationally viable. These promising trends support the ongoing investigation in a larger randomized trial, aiming to assess whether scalable, optimized digital nudges can influence real-world medication behavior and potentially improve cardiovascular outcomes.8

A systematic review of 14 studies (n = 1,785) in patients with chronic disease found that mobile app interventions significantly improved medication adherence compared to usual care (Cohen’s d = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.27–0.52; P < 0.001), with low GRADE certainty. No evidence of publication bias (P = 0.81) or substantial heterogeneity (I² = 29%) was found. Sensitivity analysis confirmed robustness (Cohen’s d = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.33–0.54; P < 0.001). Apps included nine features, most notably documentation, reminders, and data sharing. Subgroup analysis showed no significant variation in effect by app feature or study characteristic. Compared to conventional care, mobile app was effective, and its acceptability was 91.7%. Mobile apps show promise for improving adherence in chronic disease.9

Better medication adherence through nudges

Digital nudging offers a scalable and patient-centric approach to improving medication adherence by subtly shaping decision-making environments. As digital platforms increasingly become the medium through which healthcare is delivered and experienced, user interface designers—whether clinicians, developers, or care teams—act as modern-day choice architects. They have the ability not just to inform, but to influence health behavior by embedding thoughtful, behaviorally informed nudges. Importantly, the design of these interventions must be adaptable to patient needs and contexts, avoiding one-size-fits-all approaches. As the evidence base grows, the integration of behavioral design principles into mobile health tools, apps, and systems holds substantial promise in translating intention into sustained health action.

Use tools like apps, SMS reminders, or default refill settings. Identify patient barriers and apply simple, timely prompts to guide behavior without limiting choice.4

Personalize nudges based on health literacy, motivation, digital access, and context.

Track adherence data, patient (user) feedback, and tool engagement. Use A/B testing to compare outcomes—look for better adherence, fewer errors, and positive user responses.2,3,4

Yes. Nudges must be transparent, respect patient autonomy, and align with their goals. Poorly designed nudges can feel manipulative patients should always have the option to opt out.2

By embedding simple, behaviorally informed nudges—like reminders or defaults—into digital tools that guide without pressuring. Keep designs intuitive, adaptable, and respectful of patient autonomy.

1,2,4