The role of beliefs in non-adherence

- The beliefs of patients have a strong influence over their likelihood of adherence to medications

- Belief-based models have been successfully applied to a variety of health behaviors, including adherence

- Patients’ own beliefs about their treatment and their own ability to be adherent are important factors, but are not fixed: educational interventions and encouragement may lead to improvements

Beliefs have a strong influence over non-adherent behavior

Adherence to medication can be influenced by a number of important beliefs that the patient holds, including their perception of their illness, their treatment, and self-efficacy (their own capacity to adhere).1

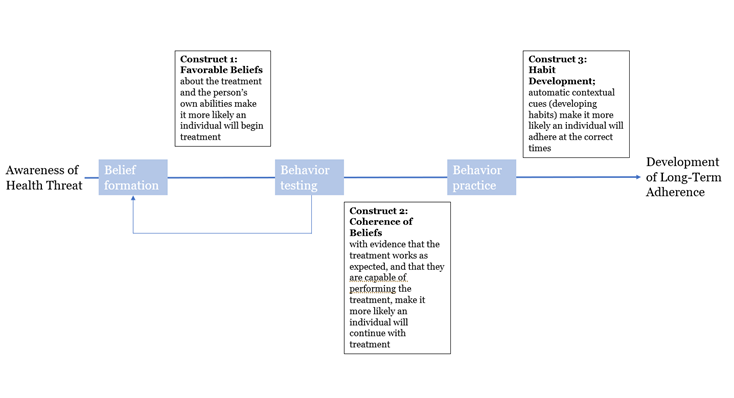

In the long term, adherence to medication requires individuals to initiate behavior based on:2

- Treatment-favorable beliefs that have formed (treatment efficacy and self-efficacy)

- Receipt of positive feedback/evidence via experience that their beliefs are true

- Repetition and practice, through which the patient develops automatic contextual cues that allow them to maintain their medication routine

The Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior are belief-based models

The Health Belief Model (HBM) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) are belief-based models that have been applied to adherence behavior.

The HBM, designed in the 1950s, has 5 core constructs:3

- Perceived severity (beliefs about seriousness of condition and its consequences)

- Perceived susceptibility (the extent to which the individual feels at risk)

- Cues to action (internal or external)

- Perceived benefits (effectiveness and availability of a particular course of action)

- Perceived barriers (negative aspects related to a particular course of action)

The TPB has been successfully applied to a variety of health behaviors, and has been shown to be predictive of adherence, suggesting that a behavior is immediately preceded by intention (i.e. motivation) to engage. This intention is influenced by a variety of factors, including attitudes to the behavior, the possibility of judgement by others (subjective norms) and perceived behavioral control.4

The Common Sense Self-Regulation Model

The common sense self-regulation model (CS-SRM) is a wide-ranging model that describes how patients develop understanding of their illness/threat to their health, and how this then affects their responses (including adherence to medication). The model is based on individual beliefs about these factors:2

- Illness identity – the label the patient uses for their illness, and its associated symptoms

- Causes – the patient’s beliefs about what causes their illness

- Timeline – what does the patient believe about the timelines of their illness (e.g. acute, chronic or cyclical)

- Consequences – the patient’s beliefs about the consequences of their illness (social/cost/health)

- Control – what the patient believes about the extent of the control that they, their medication and their healthcare professional have over their illness

Patient beliefs about their treatment

Understanding and supporting adherence is underpinned by patient beliefs about their medication, which can be grouped into two core themes:5,6

- Necessity – whether the medication is needed to maintain health, currently and into the future

- Concerns – worries about potential adverse effects, such as long-term adverse events or drug dependence

Both elements contribute to adherence; patients who believe in the necessity of their treatment and have few concerns about it are more likely to adhere, i.e. the balance shifts in favor of adherence.5–7

Intentional non-adherence is often based on patient beliefs about their treatment, e.g. its benefit, potential for side effects or the risk of becoming addicted to the medication.8 This could also be influenced by religious or ethical constraints. For example, PERT preparations are likely to be of porcine origin, which challenges individuals from certain religions, as well as vegetarians and vegans.9 This may lead to non-adherence unless the issue can be resolved.

Self-efficacy

The definition of self-efficacy is a person’s belief or confidence that they can successfully perform a specific behavior to attain a desired goal.1 It is not fixed – a patient’s self-efficacy can be altered by persuasion or encouragement. It is therefore an important element that can be targeted in improving adherence to medications.1

Self-efficacy is considered to be one of the most important general predictors of behavior change, and therefore an individual’s ability to manage their own disease, including adherence.1

Understanding the beliefs of individuals and personalizing support

Beyond assessing patient satisfaction, the ideal patient–provider relationship should bring about improvement in medication adherence, reduced healthcare utilization and cost, and improved clinical outcomes.10 Healthcare professionals should carefully evaluate individual patients in order to determine their beliefs and motivations. If this process reveals beliefs that may undermine adherence, these can be discussed and educational and encouraging strategies can be employed to modify behavior.11

Dedicated tools exist for assessing patient beliefs; these include the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire12 and the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire.6 Motivational interviewing is also used in driving conversations with patients, helping them to open up about their beliefs and discuss behavior changes. This includes asking open-ended questions that focus on the patient as an individual, including their preferences and values.